Long-term expectations

Returns from diversified equity-bond portfolios have been disappointing of late. For instance, over the last 12 months, the average of funds in the Investment Association’s three ‘mixed investment’ sectors (0-35% shares, 20-60% shares and 40-85% shares) have returned between -0.7% and 1.0%.

Increased long-term interest rates have encouraged negative returns from bond investments and acted as a headwind to stronger returns from equity investment, such that any combination of the two asset classes has resulted in muted or negative returns.

| Investment Association (IA) sector average | 12 month return |

| Mixed Investment 0-35% Shares | -0.7% |

| Mixed Investment 20-60% Shares | 0.4% |

| Mixed Investment 40-85% Shares | 1.0% |

| UK All Companies (shares) | 4.2% |

| Global (shares) | 2.6% |

| UK Gilts (government bonds) | -7.9% |

| Global Government Bonds | -6.0% |

Source: Financial Analytics (total return in GBP to 11-09-2023)

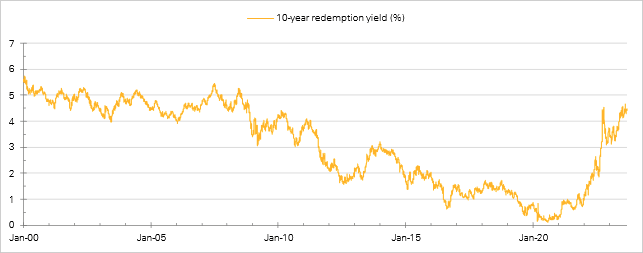

Indeed, the last 18 months or so have coincided with a period of unusual tumult in the bond market, certainly by the standards of the most recent quarter of a century. From an ‘abnormal’ low of 1.0%, long-term interest rates (as set by the market for British government bonds) have sprung back toward to a ‘more normal’ 4.5% level.

Source: Bank of England, Barras Capital Management

The abrupt increase in interest rates has had two effects. The first, as mentioned, is to act as a headwind to realised returns from both bonds and, to some extent, equities too. The second is to increase rates on offer in the market for cash (and cash-like) investments. For a period of time in recent months investors could have secured a rate of 6.2% over 12 months in a ‘Guaranteed Growth Bond’ (issue 72) at National Savings and Investments.

Accordingly, advisors are being asked why investors should commit capital to a combination of equities and bonds when cash rates are so attractive?

Assuming that those posing the question are indeed long-term investors, the answer is straightforward. It is entirely reasonable to expect investment in a combination of equities and bonds to deliver a higher return than that from cash investments over a reasonably long period of time. If investors have the benefit of time, they can use that to their advantage.

Take the most recent full decade (2012 to 2022). It’s a period of time that has born witness to a pandemic and the outbreak of war. Even so, the average fund in the IA UK All Companies sector has increased 6.0% per annum and the average fund in the IA UK Gilts sector has increased 0.6% per annum. The average fund in the IA Short Term Money Market sector, reflecting the returns available in cash and cash-like investments, has increased just 0.2% per annum over that period.

Of course, interest rates were deliberately held low for much of that decade. But the same pattern of returns emerges during other decade-long periods. This historical track record is more than mere happenstance. Riskier assets ought to provide a higher return than less risky assets.

Returning to the 2012 to 2022 decade for a moment, I count three years in which UK equities underperformed cash and four years in which UK government bonds underperformed cash. In other words, there was a lot of variability in short-term returns. Unfortunately, there is no escaping this variability.

By way of illustration, you can get a better understanding of the effect of a similar variability by finding yourself an ordinary six-sided die. Roll it 10 times and keep a running total of your score. Compare your score with my ‘expectation’ that you’ll score somewhere close to 35. It’s quite possible that you will score much higher or much lower and it is for that reason that I wouldn’t bet very much on my prediction being accurate. But over, say, 50 or 100 rolls I’d be increasingly confident that your score will coincide with an outcome equal to 3.5 x n (n being the number of rolls, 3.5 being the average of the six equally likely outcomes).

The equity and bond markets do not behave in line with our dice roll example (the distribution of returns is very much different) but it is a useful model because it illustrates the effect of short-term variability. Similarly, it illustrates what I mean when I talk about ‘expected’ returns.

When I say I ‘expect’ riskier assets to outperform less risky assets, I do it in the knowledge that returns in any one year will vary greatly but will tend toward that rate with increasing confidence over the longer-term. (With a decade or so approximating the ‘longer-term’).

At this moment, BlackRock’s ‘expected’ return for a 60-40 equity-bond portfolio over the next 10 years or so is 6.4% per annum, not far off our own expectations. That might not sound too attractive given a cash rate of 6.2% but there is a mismatch in a comparison of the two rates. The cash rate of 6.2% is only offered over the next 12 months, not every year for the next 10 years. We do not know what the return from cash will be over the next 10 years, in much the same way that we don’t know what the return will be for equities and bonds.

As it stands, prices in the bond market are consistent with expectations for the Bank of England Base Rate to move a little higher (to 5.5% or 5.75%) before declining to around 3.5% over the next 5 years or so. The closest thing to a market-based estimate for cash rates over the next 10 years is the redemption yield on the 10 year gilt, which currently stands close to 4.5% per annum; far lower than our 6.4% per annum estimate for returns on a 60-40 portfolio.

The truth is that we do not know if risky assets will provide a stronger return than less risky assets over the next 10 years. But the balance of probabilities is weighted in that direction. And that is why long-term investors ought to embrace a level of risk that is commensurate with their capacity for loss and their tolerance for risk.

Request a callback

Enter your details below and a member of our team will be in touch.